Our attorneys represent Social Security Claimants suffering with Fibromyalgia. Our lawyers travel to disability hearing offices and appear before Administrative Law Judges (ALJs) throughout the United States including Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, New Mexico, Washington and Florida.

Social Security Disability evaluates Fibromyalgia using the following Ruling.

POLICY INTERPRETATION RULING

SSR 12-2p: Titles II and XVI: Evaluation of Fibromyalgia

Purpose: This Social Security Ruling (SSR) provides guidance on how we develop evidence to establish that a person has a medically determinable impairment (MDI) of fibromyalgia (FM), and how we evaluate FM in disability claims and continuing disability reviews under titles II and XVI of the Social Security Act (Act).[1]

Citations: Sections 216(i), 223(d), 223(f), 1614(a)(3), and 1614(a)(4) of the Act, as amended; Regulations No. 4, subpart P, sections 404.1505, 404.1508– 404.1513, 404.1519a, 404.1520, 404.1520a, 404.1521, 404.1523, 404.1526, 404.1527– 404.1529, 404.1545, 404.1560– 404.1569a, 404.1593, 404.1594, appendix 1, and appendix 2; and Regulations No. 16, subpart I, sections 416.905, 416.906, 416.908-416.913, 416.919a, 416.920, 416.920a, 416.921, 416.923, 416.924, 416.924a, 416.926, 416.926a, 416.927– 416.929, 416.945, 416.960-416.969a, 416.987, 416.993, 416.994, and 416.994a.

Introduction

FM is a complex medical condition characterized primarily by widespread pain in the joints, muscles, tendons, or nearby soft tissues that has persisted for at least 3 months. FM is a common syndrome.[2] When a person seeks disability benefits due in whole or in part to FM, we must properly consider the person’s symptoms when we decide whether the person has an MDI of FM. As with any claim for disability benefits, before we find that a person with an MDI of FM is disabled, we must ensure there is sufficient objective evidence to support a finding that the person’s impairment(s) so limits the person’s functional abilities that it precludes him or her from performing any substantial gainful activity. In this Ruling, we describe the evidence we need to establish an MDI of FM and explain how we evaluate this impairment when we determine whether the person is disabled.

Policy Interpretation

FM is an MDI when it is established by appropriate medical evidence. FM can be the basis for a finding of disability.

I. What general criteria can establish that a person has an MDI of FM? Generally, a person can establish that he or she has an MDI of FM by providing evidence from an acceptable medical source.[3] A licensed physician (a medical or osteopathic doctor) is the only acceptable medical source who can provide such evidence. We cannot rely upon the physician’s diagnosis alone. The evidence must document that the physician reviewed the person’s medical history and conducted a physical exam. We will review the physician’s treatment notes to see if they are consistent with the diagnosis of FM, determine whether the person’s symptoms have improved, worsened, or remained stable over time, and establish the physician’s assessment over time of the person’s physical strength and functional abilities.

II. What specific criteria can establish that a person has an MDI of FM? We will find that a person has an MDI of FM if the physician diagnosed FM and provides the evidence we describe in section II.A. or section II. B., and the physician’s diagnosis is not inconsistent with the other evidence in the person’s case record. These sections provide two sets of criteria for diagnosing FM, which we generally base on the 1990 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia[4] (the criteria in section II.A.), or the 2010 ACR Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria[5] (the criteria in section II.B.). If we cannot find that the person has an MDI of FM but there is evidence of another MDI, we will not evaluate the impairment under this Ruling. Instead, we will evaluate it under the rules that apply for that impairment.

A. The 1990 ACR Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Based on these criteria, we may find that a person has an MDI of FM if he or she has all three of the following:

1. A history of widespread pain—that is, pain in all quadrants of the body (the right and left sides of the body, both above and below the waist) and axial skeletal pain (the cervical spine, anterior chest, thoracic spine, or low back)—that has persisted (or that persisted) for at least 3 months. The pain may fluctuate in intensity and may not always be present.

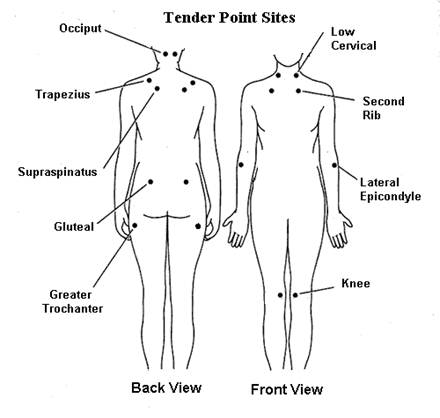

2. At least 11 positive tender points on physical examination (see diagram below). The positive tender points must be found bilaterally (on the left and right sides of the body) and both above and below the waist.

a. The 18 tender point sites are located on each side of the body at the:

- Occiput (base of the skull);

- Low cervical spine (back and side of the neck); Trapezius muscle (shoulder);

- Supraspinatus muscle (near the shoulder blade); Second rib (top of the rib cage near the sternum or breast bone);

- Lateral epicondyle (outer aspect of the elbow);

- Gluteal (top of the buttock);

- Greater trochanter (below the hip); and

- Inner aspect of the knee.

b. In testing the tender-point sites,[6] the physician should perform digital palpation with an approximate force of 9 pounds (approximately the amount of pressure needed to blanch the thumbnail of the examiner). The physician considers a tender point to be positive if the person experiences any pain when applying this amount of pressure to the site.

3. Evidence that other disorders that could cause the symptoms or signs were excluded. Other physical and mental disorders may have symptoms or signs that are the same or similar to those resulting from FM.[7] Therefore, it is common in cases involving FM to find evidence of examinations and testing that rule out other disorders that could account for the person’s symptoms and signs. Laboratory testing may include imaging and other laboratory tests (for example, complete blood counts, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, anti-nuclear antibody, thyroid function, and rheumatoid factor).

B. The 2010 ACR Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria. Based on these criteria, we may find that a person has an MDI of FM if he or she has all three of the following criteria[8]:

1. A history of widespread pain (see section II.A.1.);

2. Repeated manifestations of six or more FM symptoms, signs,[9] or co-occurring conditions,[10] especially manifestations of fatigue, cognitive or memory problems (“fibro fog”), waking unrefreshed,[11] depression, anxiety disorder, or irritable bowel syndrome; and

3. Evidence that other disorders that could cause these repeated manifestations of symptoms, signs, or co-occurring conditions were excluded (see section II.A.3.).

III. What documentation do we need?

A. General.

1. As in all claims for disability benefits, we need objective medical evidence to establish the presence of an MDI. When a person alleges FM, longitudinal records reflecting ongoing medical evaluation and treatment from acceptable medical sources are especially helpful in establishing both the existence and severity of the impairment. In cases involving FM, as in any case, we will make every reasonable effort to obtain all available, relevant evidence to ensure appropriate and thorough evaluation.

2. We will generally request evidence for the 12-month period before the date of application unless we have reason to believe that we need evidence from an earlier period, or unless the alleged onset of disability is less than 12 months before the date of application.[12] In the latter case, we may still request evidence from before the alleged onset date if we have reason to believe that it could be relevant to a finding about the existence, severity, or duration of the disorder, or to establish the onset of disability.

B. Other sources of evidence.

1. In addition to obtaining evidence from a physician, we may request evidence from other acceptable medical sources, such as psychologists, both to determine whether the person has another MDI(s) and to evaluate the severity and functional effects of FM or any of the person’s other impairments. We also may consider evidence from medical sources who are not “acceptable medical sources” to evaluate the severity and functional effects of the impairment(s).

2. Under our regulations and SSR 06-3p,[13] information from nonmedical sources can also help us evaluate the severity and functional effects of a person’s FM. This information may help us to assess the person’s ability to function day-to-day and over time. It may also help us when we make findings about the credibility of the person’s allegations about symptoms and their effects.[14] Examples of nonmedical sources include:

a. Neighbors, friends, relatives, and clergy;

b. Past employers, rehabilitation counselors, and teachers; and

c. Statements from SSA personnel who interviewed the person.

C. When There Is Insufficient Evidence for Us to Determine Whether the Person Has an MDI of FM or Is Disabled.

1. We may take one or more actions to try to resolve the insufficiency:[15]

a. We may recontact the person’s treating or other sources(s) to see if the information we need is available;

b. We may request additional existing records;

c. We may ask the person or others for more information; or

d. If the evidence is still insufficient to determine whether the person has an MDI of FM or is disabled despite our efforts to obtain additional evidence, we may make a determination or decision based on the evidence we have.

2. We may purchase a consultative examination (CE) at our expense to determine if a person has an MDI of FM or is disabled when we need this information to adjudicate the case.[16]

a. We will not purchase a CE solely to determine if a person has FM in addition to another MDI that could account for his or her symptoms.

b. We may purchase a CE to help us assess the severity and functional effects of medically determined FM or any other impairment(s). If necessary, we may purchase a CE to help us determine whether the impairment(s) meets the duration requirement.

c. Because the symptoms and signs of FM may vary in severity over time and may even be absent on some days, it is important that the medical source who conducts the CE has access to longitudinal information about the person. However, we may rely on the CE report even if the person who conducts the CE did not have access to longitudinal evidence if we determine that the CE is the most probative evidence in the case record.

IV. How do we evaluate a person’s statements about his or her symptoms and functional limitations?

We follow the two-step process set forth in our regulations and in SSR 96-7p.[17]

A. First step of the symptom evaluation process. There must be medical signs and findings that show the person has an MDI(s) which could reasonably be expected to produce the pain or other symptoms alleged. FM which we determined to be an MDI satisfies the first step of our two-step process for evaluating symptoms.

B. Second step of the symptom evaluation process. Once an MDI is established, we then evaluate the intensity and persistence of the person’s pain or any other symptoms and determine the extent to which the symptoms limit the person’s capacity for work. If objective medical evidence does not substantiate the person’s statements about the intensity, persistence, and functionally limiting effects of symptoms, we consider all of the evidence in the case record, including the person’s daily activities, medications or other treatments the person uses, or has used, to alleviate symptoms; the nature and frequency of the person’s attempts to obtain medical treatment for symptoms; and statements by other people about the person’s symptoms. As we explain in SSR 96-7p, we will make a finding about the credibility of the person’s statements regarding the effects of his or her symptoms on functioning. We will make every reasonable effort to obtain available information that could help us assess the credibility of the person’s statements.

V. How do we find a person disabled based on an MDI of FM?

Once we establish that a person has an MDI of FM, we will consider it in the sequential evaluation process to determine whether the person is disabled. As we explain in section VI. below, we consider the severity of the impairment, whether the impairment medically equals the requirements of a listed impairment, and whether the impairment prevents the person from doing his or her past relevant work or other work that exists in significant numbers in the national economy.

VI. How do we consider FM in the sequential evaluation process?[18]

As with any adult claim for disability benefits, we use a 5-step sequential evaluation process to determine whether an adult with an MDI of FM is disabled.[19]

A. At step 1, we consider the person’s work activity. If a person with FM is doing substantial gainful activity, we find that he or she is not disabled.

B. At step 2, we consider whether the person has a “severe” MDI(s). If we find that the person has an MDI that could reasonably be expected to produce the pain or other symptoms the person alleges, we will consider those symptom(s) in deciding whether the person’s impairment(s) is severe. If the person’s pain or other symptoms cause a limitation or restriction that has more than a minimal effect on the ability to perform basic work activities, we will find that the person has a severe impairment(s).[20]

C. At step 3, we consider whether the person’s impairment(s) meets or medically equals the criteria of any of the listings in the Listing of Impairments in appendix 1, subpart P of 20 CFR part 404 (appendix 1). FM cannot meet a listing in appendix 1 because FM is not a listed impairment. At step 3, therefore, we determine whether FM medically equals a listing (for example, listing 14.09D in the listing for inflammatory arthritis), or whether it medically equals a listing in combination with at least one other medically determinable impairment.

D. Residual Functional Capacity (RFC) assessment: In our regulations and SSR 96-8p,[21] we explain that we assess a person’s RFC when the person’s impairment(s) does not meet or equal a listed impairment. We base our RFC assessment on all relevant evidence in the case record. We consider the effects of all of the person’s medically determinable impairments, including impairments that are “not severe.” For a person with FM, we will consider a longitudinal record whenever possible because the symptoms of FM can wax and wane so that a person may have “bad days and good days.”

E. At steps 4 and 5, we use our RFC assessment to determine whether the person is capable of doing any past relevant work (step 4) or any other work that exists in significant numbers in the national economy (step 5). If the person is able to do any past relevant work, we find that he or she is not disabled. If the person is not able to do any past relevant work or does not have such work experience, we determine whether he or she can do any other work. The usual vocational considerations apply.[22]

1. Widespread pain and other symptoms associated with FM, such as fatigue, may result in exertional limitations that prevent a person from doing the full range of unskilled work in one or more of the exertional categories in appendix 2 of subpart P of part 404 (appendix 2).[23] People with FM may also have nonexertional physical or mental limitations because of their pain or other symptoms.[24] Some may have environmental restrictions, which are also nonexertional.

2. Adjudicators must be alert to the possibility that there may be exertional or nonexertional (for example, postural or environmental) limitations that erode a person’s occupational base sufficiently to preclude the use of a rule in appendix 2 to direct a decision. In such cases, adjudicators must use the rules in appendix 2 as a framework for decision-making and may need to consult a vocational resource.[25]

DATES: Effective Date: This SSR is effective on July 25, 2012.

Cross-References: SSR 82-63: Titles II and XVI: Medical-Vocational Profiles Showing an Inability To Make an Adjustment to Other Work; SSR 83-12: Title II and XVI: Capability To Do Other Work—The Medical-Vocational Rules as a Framework for Evaluating Exertional Limitations Within a Range of Work or Between Ranges of Work; SSR 83-14: Titles II and XVI: Capability To Do Other Work—The Medical-Vocational Rules as a Framework for Evaluating a Combination of Exertional and Nonexertional Impairments; SSR 85-15: Titles II and XVI: Capability To Do Other Work—The Medical-Vocational Rules as a Framework for Evaluating Solely Nonexertional Impairments; SSR 96-3p: Titles II and XVI: Considering Allegations of Pain and Other Symptoms in Determining Whether a Medically Determinable Impairment is Severe; SSR 96-4p: Policy Interpretation Ruling Titles II and XVI: Symptoms, Medically Determinable Physical and Mental Impairments, and Exertional and Nonexertional Limitations; SSR 96-7p: Titles II and XVI: Evaluation of Symptoms in Disability Claims: Assessing the Credibility of an Individual’s Statements; SSR 96-8p: Titles II and XVI: Assessing Residual Functional Capacity in Initial Claims; SSR 96-9p, Titles II and XVI: Determining Capability to Do Other Work—Implications of a Residual Functional Capacity for Less Than a Full Range of Sedentary Work; SSR 99-2p: Titles II and XVI: Evaluating Cases Involving Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS); SSR 02-2p: Titles II and XVI: Evaluation of Interstitial Cystitis; and SSR 06-3p: Titles II and XVI: Considering Opinions and Other Evidence from Sources Who Are Not “Acceptable Medical Sources” in Disability Claims; Considering Decisions on Disability by Other Governmental and Nongovernmental Agencies; and Program Operations Manual System (POMS) DI 22505.001, DI 22505.003, DI 24510.057, DI 24515.012, DI 24515.061-DI 24515.063, DI 24515.075, DI 24555.001, DI 25010.001, and DI 25025.001.

[1] For simplicity, we refer in this SSR only to initial claims for benefits made by adults (individuals who are at least age 18). However, the policy interpretations in this SSR also apply to claims for benefits made by children (individuals under age 18) under title XVI of the Act and to claims above the initial level. FM can affect children, and the signs and symptoms are essentially the same in children as adults. The policy interpretations in this SSR also apply to continuing disability reviews of adults and children under sections 223(f) and 1614(a)(4) of the Act, and to redeterminations of eligibility for benefits we make in accordance with section 1614(a)(3)(H) of the Act when a child who is receiving title XVI childhood disability benefits attains age 18.

[2] See National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Fibromyalgia, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0001463.

[3] See 20 CFR 404.1513(a) and 416.913(a).

[4] See Frederick Wolfe et al., The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia: Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee, 33 Arthritis and Rheumatism 160 (1990), available at http://www.rheumatology.org/practice/clinical/classification/fibromyalgia/1990_Criteria_for_Classification_Fibro.pdf.

[5] See Frederick Wolfe et al., The American College of Rheumatology Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia and Measurement of Symptom Severity, 62 Arthritis Care & Research 600 (2010), available at http://www.rheumatology.org/practice/clinical/classification/fibromyalgia/2010_Preliminary_Diagnostic_Criteria.pdf.

[6] We may use the criteria in section II.B. of this SSR to determine an MDI of FM if the case record does not include a report of the results of tender-point testing, or the report does not describe the number and location on the body of the positive tender points.

[7] Some examples of other disorders that may have symptoms or signs that are the same or similar to those resulting from FM include rheumatologic disorders, myofacial pain syndrome, polymyalgia rheumatica, chronic Lyme disease, and cervical hyperextension-associated or hyperflexion-associated disorders.

[8] We adapted the criteria from the 2010 ACR Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria because the Act and our regulations require a claimant for disability benefits to establish by objective medical evidence that he or she has a medically determinable impairment. See sections 223(d)(5)(A) and 1614(a)(3)(D) of the Act; 20 CFR 404.1508 and 416.908; SSR 96-4p: Titles II and XVI: Symptoms, Medically Determinable Physical and Mental Impairments, and Exertional and Nonexertional Limitations, 61 FR 34488 (July 2, 1996) (also available at: http://www.socialsecurity.gov/OP_Home/rulings/di/01/SSR96-04-di-01.html).

[9] Symptoms and signs that may be considered include the “(s)omatic symptoms” referred to in Table No. 4, “Fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria,” in the 2010 ACR Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria. We consider some of the “somatic symptoms” listed in Table No. 4 to be “signs” under 20 C.F.R. 404.1528(b) and 416.928(b). These “somatic symptoms” include muscle pain, irritable bowel syndrome, fatigue or tiredness, thinking or remembering problems, muscle weakness, headache, pain or cramps in the abdomen, numbness or tingling, dizziness, insomnia, depression, constipation, pain in the upper abdomen, nausea, nervousness, chest pain, blurred vision, fever, diarrhea, dry mouth, itching, wheezing, Raynaud’s phenomenon, hives or welts, ringing in the ears, vomiting, heartburn, oral ulcers, loss of taste, change in taste, seizures, dry eyes, shortness of breath, loss of appetite, rash, sun sensitivity, hearing difficulties, easy bruising, hair loss, frequent urination, or bladder spasms.

[10] Some co-occurring conditions that may be considered are referred to in Table No. 4, “Fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria,” in the 2010 ACR Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria as “somatic symptoms,” such as irritable bowel syndrome or depression. Other co-occurring conditions, which are not listed in Table No. 4, may also be considered, such as anxiety disorder, chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bladder syndrome, interstitial cystitis, temporomandibular joint disorder, gastroesophageal reflux disorder, migraine, or restless leg syndrome.

[11] “Waking unrefreshed” may be indicated in the case record by the person’s statements describing a history of non-restorative sleep, such as statements about waking up tired or having difficulty remaining awake during the day, or other statements or evidence in the record reflecting that the person has a history of non-restorative sleep.

[12] See 20 CFR 404.1512(d) and 416.912(d).

[13] See 20 CFR 404.1513(d)(4), 416.913(d)(4); SSR 06-3p: Titles II and XVI: Considering Opinions and Other Evidence from Sources Who Are Not “Acceptable Medical Sources” in Disability Claims, 71 FR 45593 (August 9, 2006), (also available at: http://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/rulings/di/01/SSR2006-03-di-01.html).

[14] See section IV below.

[15] See 20 CFR 404.1520b(c) and 416.920b(c).

[16] See 20 CFR 404.1520b(c)(3), and 416.920b(c)(3). We may purchase a CE without recontacting a person’s treating or other sources if the source cannot provide the necessary information, or the information is not available from the source. See 20 CFR 404.1519a(b), and 416.919a(b).

[17] See 20 CFR 404.1529(b) and (c) and 416.929(b). and (c); SSR 96-7p: Titles II and XVI: Evaluation of Symptoms in Disability Claims: Assessing the Credibility of an Individual’s Statements, 61 FR 34483 (July 2, 1996) (also available at: http://www.socialsecurity.gov/OP_Home/rulings/di/01/SSR96-07-di-01.html).

[18] As we have already noted, we refer in this SSR only to adult disability claims, but the guidance in the SSR applies to all disability cases under titles II and XVI involving FM. We use different sequential evaluation processes for claims of children under title XVI and in continuing disability reviews of adults and children under titles II and XVI. See 20 CFR 404.1594, 416.924, 416.994, and 416.994a. We also use a modification of the 5-step sequential evaluation process for adults in 20 CFR 416.920 when we do age-18 redeterminations under title XVI. See 20 CFR 416.987.

[19] See 20 CFR 404.1520 and 416.920.

[20] See SSR 96-3p: Titles II and XVI: Considering Allegations of Pain and Other Symptoms in Determining Whether a Medically Determinable Impairment is Severe, 61 FR 34468 (July 2, 1996) (also available at: http://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/rulings/di/01/SSR96-03-di-01.html).

[21] See 20 CFR 404.1520(e), 416.920(e); SSR 96-8p: Titles II and XVI: Assessing Residual Functional Capacity in Initial Claims, 61 FR 34474 (July 2, 1996) (also available at: http://www.socialsecurity.gov/OP_Home/rulings/di/01/SSR96-08-di-01.html).

[22] See 20 CFR 404.1560– 404.1569a and 416.960– 416.969a.

[23] See SSR 83-12: Title II and XVI: Capability To Do Other Work—The Medical-Vocational Rules as a Framework for Evaluating Exertional Limitations Within a Range of Work or Between Ranges of Work (available at http://www.socialsecurity.gov/OP_Home/rulings/di/02/SSR83-12-di-02.html).

[24] See SSR 85-15: Titles II and XVI: Capability To Do Other Work—The Medical-Vocational Rules as a Framework for Evaluating Solely Nonexertional Impairments, (available at: http://www.socialsecurity.gov/OP_Home/rulings/di/02/SSR85-15-di-02.html); and SSR 96-4p.

[25] See SSR 83-12; SSR 83-14: Titles II and XVI: Capability To Do Other Work—The Medical-Vocational Rules as a Framework for Evaluating a Combination of Exertional and Nonexertional Impairments (available at http://www.socialsecurity.gov/OP_Home/rulings/di/02/SSR83-14-di-02.html); SSR 85-15; and SSR 96-9p, Titles II and XVI: Determining Capability to Do Other Work—Implications of a Residual Functional Capacity for Less Than a Full Range of Sedentary Work, 61 FR 34478 (July 2, 1996) (also available at: http://www.socialsecurity.gov/OP_Home/rulings/di/01/SSR96-09-di-01.html).